📈 The Game Concept Ramp-Up

Making games is hard.

Sometimes it takes months, even years, to determine if your game concept is solid (or not).

But what if we chopped up the process into manageable bits?

I'm calling this the game concept ramp-up. It's a list of tasks that you can complete when working on a new game concept, ordered from least to most difficult and/or time-consuming.

How this list works

The first step should be the easiest. Each step generally increases in either difficulty or time to complete. After each step, you should have something tangible & useful to you in the game development process.

Most stated numbers like "3-5 words" or "60 seconds" are also arbitrary – just hit the marks that work for you.

- Describe your game using one sentence

- Write a short description for your game

- Decide on the genre(s) for your game

- List 3-5 popular games that are similar to yours

- Produce a color palette for your game

- Create a 16x16 pixel favicon for your game

- List all the action verbs players can perform

- Create a single-page GDD (game design document)

- Create a single screenshot to represent your game

- Make a 3-second GIF that sells your game

- Build a rough prototype (quick game-jam style)

- Create a gameplay-only 17-second trailer for your game

- Playtest your rough prototype

- Make a 60-second trailer that sells your game

- Create a landing page for your game

- Finish your GDD

- Create/commission key art for your game

- Create a 10-20 slide pitch deck that sells your game

- Build a fully polished, 25+ minute demo of your game

- Create a fully playable, 2+ hour vertical slice of your game

What's cool about this list is that you can bail at any time. If at any point you realize the concept isn't strong enough to justify the remaining work to get the next task done, just shelve that concept. Move on to the next one.

How we'll tackle this list

This is a long list, so let's break it down step-by-step, providing examples using my game Pixel Washer. For now we'll cover the first 10; stay tuned for the back 10!

1. Describe your game using one sentence

Explaining your game concept in just one sentence helps to distill your concept and keep scope in check.

Here's one for Pixel Washer:

You're a pig who loves power-washing beautiful pixels in an adorable piggy town!

2. Write a short description for your game

Writing a short description of your game lets you expand your vision just a little bit from the single sentence. Even this early step can be sobering – is this description "good enough" to sell your game to its intended audience?

Is it understandable, brief, exciting to the right players?

I'll tweak this over time, but this is the current short description on the Pixel Washer Steam page:

Pixel Washer is a cozy, zen-like game where you play as a cute piggy power washing beautiful pixelated worlds. Wash dirty sprites, upgrade your power washer, and clean up this filthy town.

3. Decide on the genre(s) for your game

This is difficult because you might not know for sure just yet.

Are you making a side-scrolling platformer? Turn-based RPG? Walking simulator?

The genre is important because it determines so many other things: how your game will play, how you'll make it, what kinds of art styles would be appropriate, who might want to play your game, and the list goes on.

To move forward with your concept, you've gotta pick something, so just put pen to paper. For Pixel Washer, I decided it was going to be a casual overhead shooter with minimal simulator features.

4. List 3-5 popular games that are similar to yours

Here in these parts, we call these "comps" or "comparable games" but you can call them whatever you want! Just make a short list of the sorts of games whose players would likely also be interested in your game.

This will be more difficult if you're making a highly experimental game. If you can, try to pick games that are of similar-ish genres, art styles, and/or quality bars as what you're trying to build.

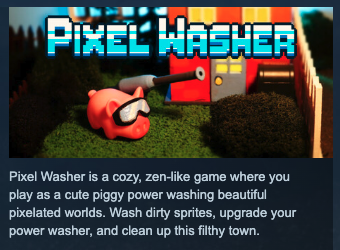

Pixel Washer's comps include:

- PowerWash Simulator (obviously)

- Unpacking (because it's zen, satisfying, and pixel art)

- Sticky Business (joy, cozy, small business ... fairly similar-ish!)

Having a handful of similar-ish games can be super handy for solidifying your vision, your scope, and for communicating about your concept. Do some research!

5. Produce a color palette for your game

Making a color palette is fun! It also helps you solidify your direction, your mood, and the look/feel of your game. It can help inform the aesthetics of your game of course, but also your branding, your promotional assets, your landing page, a pitch deck, and more.

I created a color palette based on the primary pixel art assets packs I've been using to develop Pixel Washer. From my experience you might find 16 colors to be a bit restrictive, but don't go too high; 32-64 colors should be plenty.

See the UFO 50 Palette - 50 games with just 32 colors! Impressive.

If you need help with this, try the palette generators Coolors or Poline, or read a guide to Color Theory. Have fun with it!

6. Create a 16x16 pixel favicon for your game

This was pretty straightforward for me because I've got Pigxel, the power washing pig. Pigxel fits perfectly into the 16x16 image:

Using your palette from the previous step, try to come up with a 16x16 visual that represents your game, sets the mood, and/or is simply nice to look at. Yes, 16x16 is tiny, but these little images are still used today – see your browser tab! That's a favicon, and some platforms request them.

The tight restriction here can actually help jumpstart your creativity!

7. List all the action verbs players can perform

I always struggle with this. Being able to list your game's verbs feels somewhat childish to me, maybe because it reminds me of learning sentence structure in elementary school or something.

IDK, but it's helpful, and worth doing!

I think (?) Pixel Washer's verbs are:

Move, run, equip, choose, aim, wash, push, purchase, exit, navigate.

That sounds right.

I mean, we're designing this game, so we should know everything that players are able to do, right? Doing this can reveal when your game is doing too much – or not enough. From my experience, there's often more things players can do than we may have thought before enumerating all of them.

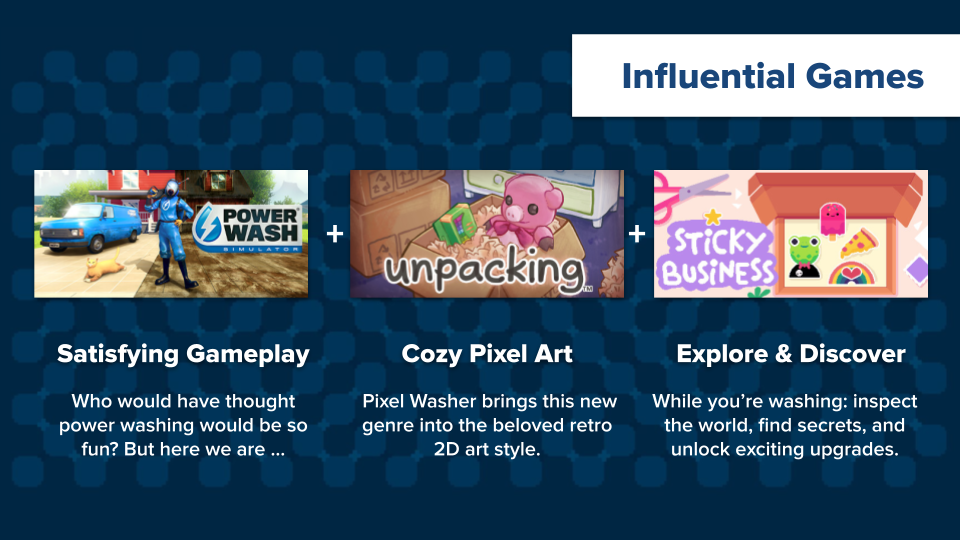

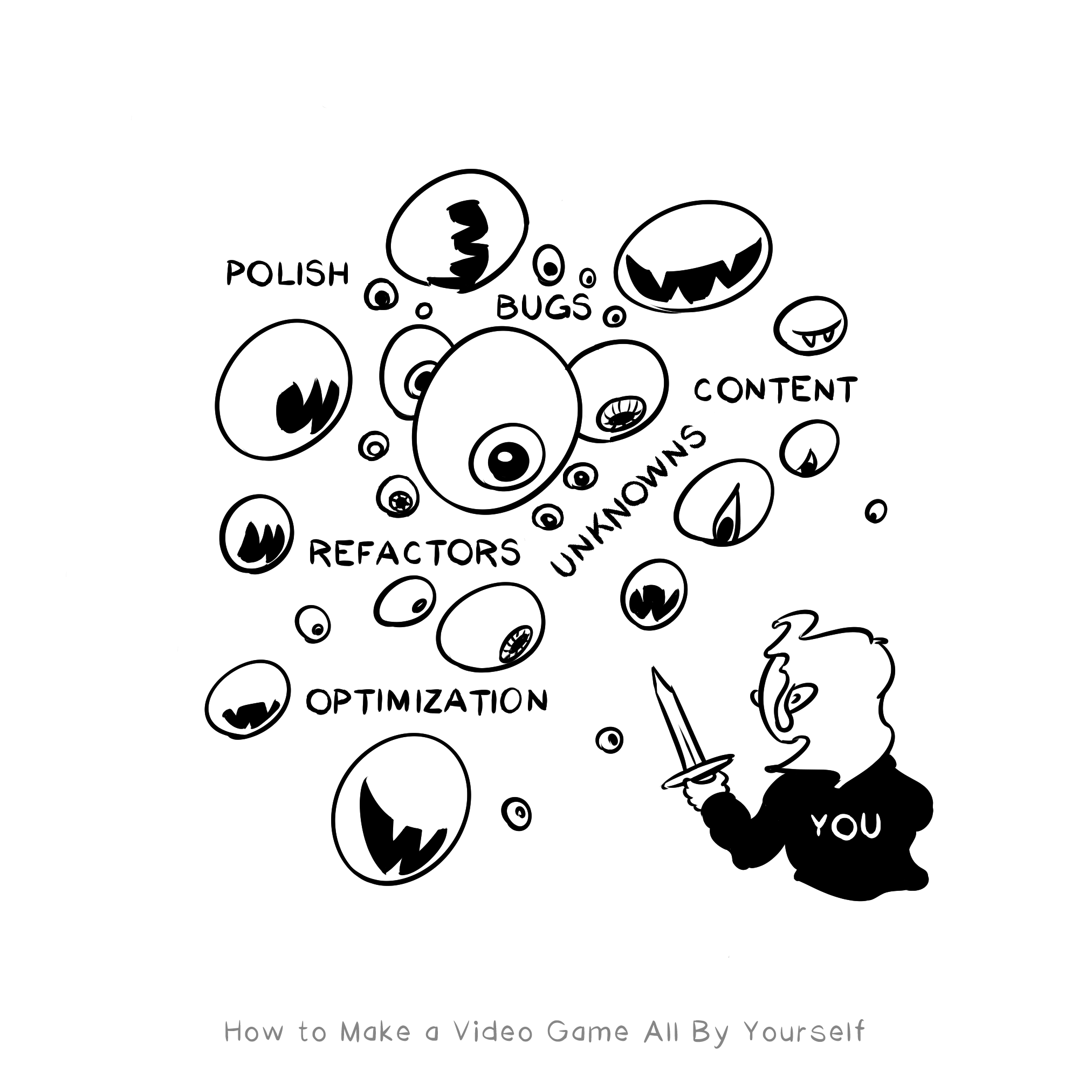

Keep in mind that each of these verbs needs to be thoughtfully designed and developed. Doing this can feel tedious but it can help us avoid the dreaded scope creep, which is one of our hardest bosses.

8. Create a single-page GDD (game design document)

This is hard because you've gotta nail down the game. How dare someone ask this of us?! I know. As if we know what we're going to build ...

Some developers view a GDD as mandatory, something they can't imagine working without. Others have never in their lives made one, and would only do so if contractually required to do it (hello, oops, that's me).

The reality is that many of us kind of "wing it" or otherwise depend upon our good instincts to safely navigate us through the rough waters of game development.

We'll expand upon this later so for now, just bang out a few paragraphs that describe how your game plays. Here's a section from Pixel Washer's GDD:

Pixel Washer is a casual overhead action game wrapped up in a simple business simulator.

Players begin in their headquarters, choose jobs to accept, power wash those locations, earn money, then purchase upgrades. The game emphasizes relaxing gameplay, progression, and an underlying story about family and cleanliness.

9. Create a single screenshot to represent your game

Naturally I already did this for Pixel Washer: 3-day devlog, here it is:

This early screenshot was just made in my pixel paint program (Clip Studio Paint), but it doesn't look too far off from how the actual game is turning out to look.

Making a screenshot is so helpful for solidifying your vision of your game. It can help you pick a resolution, an art style, answer questions about your user interface, and more.

10. Make a 3-second GIF that sells your game

I also made this during my Pixel Washer: 3-day devlog, here's that:

This was technically made using "game code" but it was really hacked-up. I used LÖVE because I had already prototyped something workable (for another project with Geoff Blair).

The purpose of your GIF is to show a quick animation of the gameplay. This is when you can really start to get a feel for how your game will play.

I'm a big advocate for GIFs, as you might know if you caught my GDC talk Content-Ready Game Development (look at that plug!).

Early GIFs of Pixel Washer gameplay

What's cool about this list is that you can bail at any time. If at any point you realize the concept isn't strong enough to justify the remaining work to get the next task done, just shelve that concept. Move on to the next one.

Again, find those first 10 steps with explanations right here. Now let's continue the list:

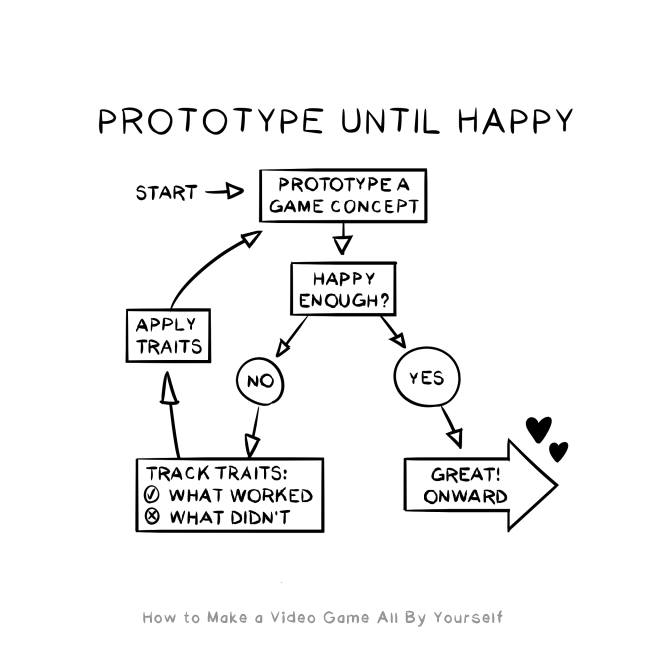

11. Build a rough prototype (quick game-jam style)

My advice is to treat this exactly like a game jam.

That's how I did it! I had a 3-day weekend and decided to jam out a few of the steps listed in this guide. It was fun and taught me a lot about my concept.

This was one of my first videos for Valadria so don't expect much

You could of course pick an actual game jam and contribute to it. Game devs have shown this to be a winning approach over and over and over and over again.

My advice is to develop your prototype quick and dirty! Read those words again. I know that "quick and dirty" is a common expression but I'm dead serious here.

Quick. Dirty. Do not be tempted to re-use this code for anything else. Make it as fast and sloppy as necessary to just get the basic prototype out. If you decide to develop this game further, be prepared to start from scratch with better code.

This is probably one of the hardest steps. Free yourself. Be dirty. Good luck!

12. Create a gameplay-only 17-second trailer for your game

Trailers are the perfect way to promote your game. Typically they're around 60-90 seconds, which can be a big ask without having built most of the game.

Making a shorter trailer is much easier, but can still help promote your game.

I did this! It was for INDIE Live Expo, and you can watch it below:

Isn't it just so much easier to make a trailer than an entire video game?! (Yes.)

Which begs the question ... should trailer-led game development be more of a thing? (Probably.)

The idea is that, instead of spending weeks or months making an entire game, you quickly make a trailer in just a few days or whatever. Then, blast that out all over the web to see what people think.

Did they love it? Did it go viral? Or do you at least now have loads of positive comments? Either way making a trailer can be a far faster method of determining if the concept you're developing is gold (or not).

I'm starting to think game devs should use trailer led game development.

— Mike Diskett (@MikeDiskett) May 18, 2024

Make a trailer, if it gets traction then make the game.

Trailer led game development. Sounds like a good idea!

13. Playtest your rough prototype

Look, I'm going to level with you: indies don't playtest enough.

Statistically, this includes you. (It certainly includes me. Hah.)

Even if all you do is sit down with a friend (or video chat with them), make them play your game, shut your mouth, and take good notes – you are head and shoulders above most indies.

Yes, really.

If you go the extra mile and do a "professional" (paid) playtest?! Forget about it! You're on another level. You're learning more about the reality of playing your game from real players, you're finding/fixing more bugs, and you're making your game far better than you could on your own.

I did a playtest for Pixel Washer. It was early times, but it was time, ya know? I booked 10 participants, each recording 30 minutes of video, for a whopping total of 5 hours worth of playtester videos. They also filled out feedback surveys!

I consumed all of their feedback, bored out of my mind, sobbing uncontrollably, agonizing over my stupid decisions, banging my head against – I'm just kidding it wasn't that bad. But it's certainly painful to watch players struggle with your game (or just not enjoy it).

It's hard but it's worth doing. So just do it!

I got "fancy" with it for Pixel Washer. I used Game Tester and integrated with their API – but you do you. Figure out what works for you, recruit from the Valadria Discord if you're strapped for cash, and get the feedback you desperately need to make your game better.

14. Make a 60-second trailer that sells your game

Here's my trailer, clocking in just under 50 seconds.

Yup, I did a weird "chilled-out guy" voice (with effects) to narrate it. Why did I do that, you ask? Well, I, uh ... gotta go! Byeeeeeeee

True, it's a weird trailer. I'm agreeing with you!

If you need advice on making game trailers, you know I'm going to point you to Derek Lieu and our podcast all about indie game trailers.

15. Create a landing page for your game

Eventually you must have some place for players to learn about your game. Ideally it's on a domain you own, but you'll need store page(s) either way. What will your pages look like? How do you talk about your game, how do you convince players it's worthwhile?

There are lots of different options for your landing page(s). Here's what you could do, and what I've done for Pixel Washer:

- A landing page that you own. Here's mine (includes a press kit!).

- Itch is great, isn't it? Here are some tools for making good Itch pages.

- Steam is probably the ideal place, but you might not feel ready yet. That's OK! It's a big deal – hold out until you know for sure what kind of game you're making, what it looks like, and have some attractive assets ready to post.

- A vanity URL? Sure, do it, if it motivates you. I got pixelwasher.com.

Pixel Washer's landing page on valadria.com

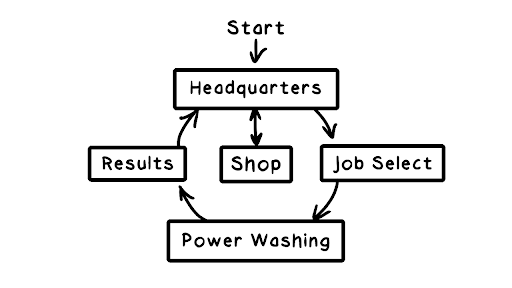

16. Finish your GDD (Game Design Document)

This is hard because you've really gotta nail down the whole game. How dare someone ask this of us?! I know!! We've already written up a whole entire page, and now we have to flesh it out?! Ridiculous.

I have a "full" GDD for Pixel Washer, and yes I had to make it. Someday I might share it but for now I neither can nor want to, but I will share a drawing I made for it.

This shows the basic game loop, which is that you start at your business's headquarters, your select a job to wash, you do the actual washing, you get to see your results (and get paid), and then you head back to your headquarters. Here you have the option of visiting the shop where you can buy stuff.

That's the game. Obviously there's more to it, but that's a great way to break it down. If you're struggling to make a GDD, just make it a simple document that describes the game, and maybe include a flowchart drawing the way I have.

Don't overthink it. Finish a first draft and iterate on it later.

17. Create/commission key art for your game

Are you among the almost exactly 300 people who follow me and my work closely enough to watch a long, self-indulgent video about my barely-games-adjacent side project about photographing a hand-painted diorama to promote my indie game?

Since you're here, allow me to say that I really appreciate you. Seriously, thanks!

Grateful for all 343 viewers

Anyway I created key art for Pixel Washer myself, because of reasons I discuss in the video. If you're smarter and/or wealthier than me, you should probably commission key art for your game from a real artist.

This can help make your project feel "real" in that you've now spent nontrivial money (and/or time) on your project. And you've got some beautiful artwork to help promote it!

This step can be difficult to take – how do you find an artist? How much do you pay them? Why don't you just take diorama photos like that weird Matt guy? You can get the ball rolling by finding games whose artwork you admire, then finding out who made their art.

Select photos from 🔥 Steam Game Promo Art - Photography and Fire

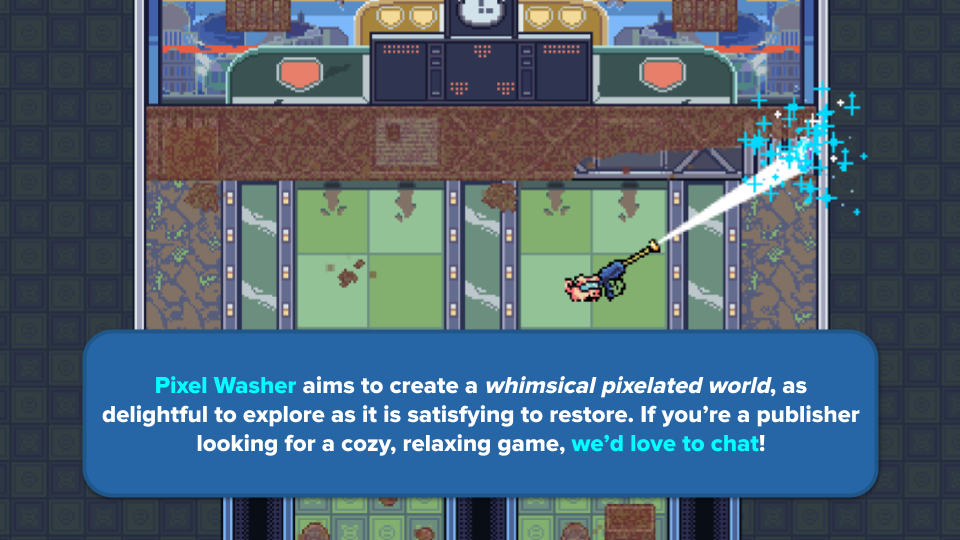

18. Create a 10-20 slide pitch deck for your game

A pitch deck is meant to explain your game and how you plan to make it. It should be attractive, fun to read, and answer most questions anyone might have about your game (especially publishers).

Ideally they have sections on genre, comps, development plan, timelines, marketing thoughts, maybe a budget, and whatever else is appropriate for your project.

I'd like to share mine someday. Maybe! (Stay tuned.) In the meantime, here are some select slides from the Pixel Washer pitch deck:

Slides from the Pixel Washer pitch deck

Here are some resources on pitch decks:

- The Only 10 Slides You Need in Your Pitch

- 30 Things I Hate About Your Game Pitch

- GameDiscoverCo Plus - Pitch Decks

- Glitch / Video Game Pitch Decks

If you're working on a pitch deck, you should chat with my friend Sean McKenzie

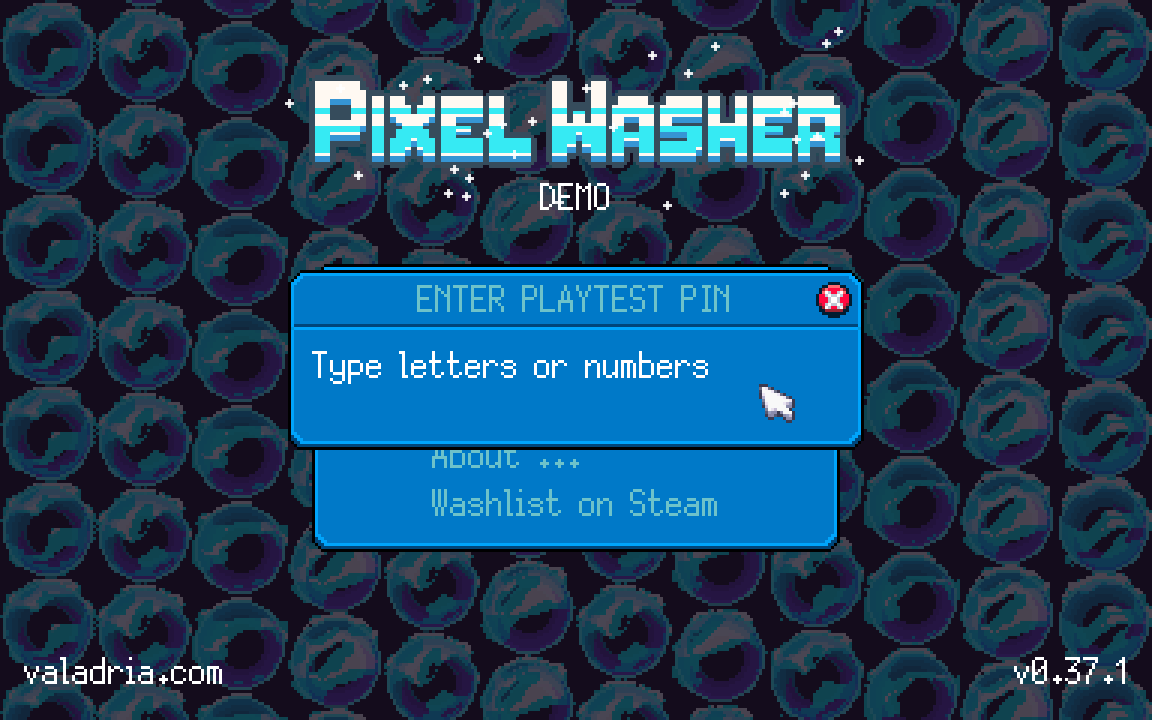

19. Build a fully polished, 25+ minute demo of your game

The Pixel Washer demo is (currently) on Itch. It's very simple but gets the idea across, I think.

I might take this down soon. It's out of date and I'm not ready to show the new stuff yet

I would not recommend expanding your quick 'n dirty prototype to make your demo. I mean you do you, I don't know how you like to make games, but you should take your demo more seriously than your prototype.

Your demo can be very short, but it should be completely playable. At this point, players who will eventually be big fans of your game should enjoy the demo. If they don't, then something is wrong.

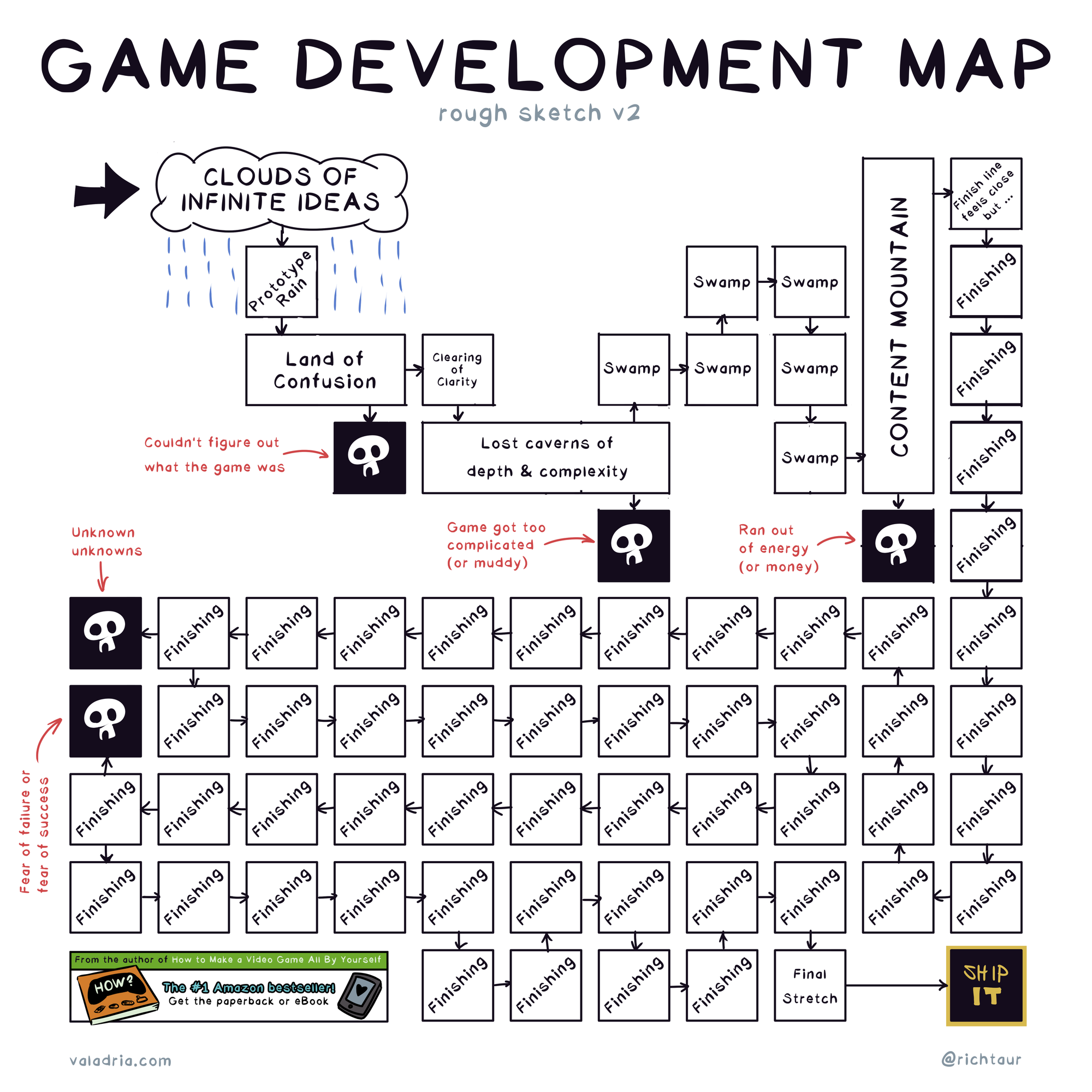

This is kind of the "last stop" before continuing into "the swamp" of seemingly-endless development cycles towards the finish line. It might feel like you've done a ton of work to arrive at this point (and you have, good job!), but it's nothing compared to the months or years of finishing. 💀

This is the time to solve those major problems ... or abandon this particular concept.

20-99. Finish and release your game

That's it! Now you just need to finish it bahahahahaha of course that's the hardest part. If you'd like a guide on that wellllll conveniently I wrote a book about that.

🧪 Test your steps

At each step during the process, you can vet your concept. Ask friends, post your progress online, and see what kind of feedback you get. If you like what you see, keep going!

Grateful for this early Pixel Washer feedback. They give me energy 🔥

If you don't get the positive reaction you're looking for, then: take notes, think about how to improve, and get back to the drawing board. See ya there!